Local History

Read about local history and the people and events that contributed to Lough Arrow.

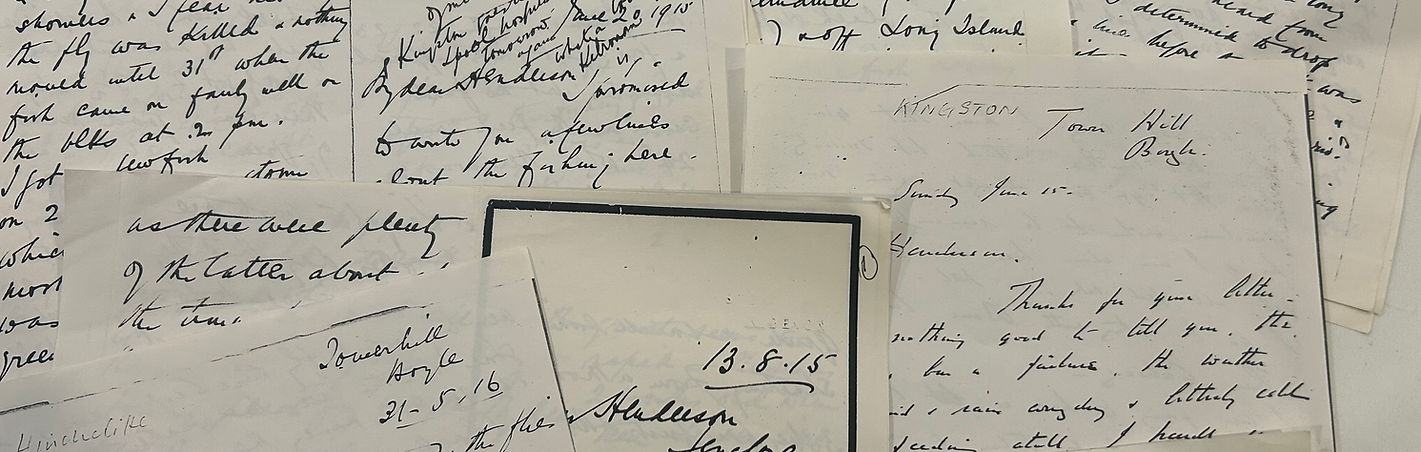

The Henderson Letters

Between 1914 and 1922, as the world convulsed in the turmoil of the Great War, another story was unfolding, one not of trenches or treaties but of trout and hatching fly, of whispers across still waters and friendships sealed in ink and cast line. These letters tell the stories of a remarkable group of anglers that fished Ireland’s western lakes, particularly Lough Arrow. Lord Kingston, John Henderson, Frank B. Hinchcliff, Leonard Brooks, and Martin E. Mosely, each a passionate sportsman, they formed a close-knit community bound by innovation, observation, and early conservation efforts.

Many honed their fly fishing skills on England’s chalk streams before bringing refined dry fly techniques to Ireland, adapting them to the challenges of Lough fishing with shifting winds, shallow bays, and large, elusive trout. Their experimentation, fly design, and meticulous record keeping helped establish Lough Arrow as a proving ground for modern lough dry fly fishing and as a result Lough Arrow can rightly be regarded as the home of Stillwater dry fly fishing.

The significance of their work was underscored when John Henderson Sr. contributed a chapter to Frederic M. Halford’s The Dry-Fly Man’s Handbook (1913), titled "Dry Fly on Lough Arrow", reinforcing Lough Arrow’s influence on the evolution of Stillwater angling. As Henderson observed:

"The spent gnat is the great attraction on Lough Arrow, and a good imitation of it, properly fished, will often kill the heaviest fish. I know of no better water for large trout taking the dry-fly in the open."

The letters that follow, written from lodges, boats, and guest houses between the anglers, capture the spirit of this era. They document fly hatches, weather patterns, conservation concerns, and personal reflections, preserving an invaluable chapter in Irish angling history.

About the Authors

Lord Kingston – Owner of Annacloy House, a lodge on Lough Arrow’s shore. An early patron of the Lough Arrow Fish Preservation Society, he kept detailed records of his outings and promoted conservation.

John Henderson Sr. – A dry fly expert and fly tyer credited with developing specialized patterns for the lake. His insights in The Dry-Fly Man’s Handbook helped define Stillwater techniques.

F.B. Hinchcliff – An English angler with a scientific approach, recording observations on fly life, trout feeding, and weather patterns.

Leonard Brooks – A dedicated English correspondent, contributing seasonal observations on fly hatches, fly-tying, and entomology.

Martin E. Mosely – A leading entomologist and fly fisher, known for his studies on aquatic insects. His book The Dry-Fly Fisherman’s Entomology (1921) became a key reference.

Lough Arrow & The Flyfishers’ Club London

These men were deeply involved in both the Lough Arrow Club (founded in 1904) and the Fly fishers’ Club of London. Through their efforts, Lough Arrow gained recognition as a premier destination for skilled dry fly anglers. The lake became a testing ground for new techniques and fly patterns, including the famed Lough Arrow spent gnat. Their correspondence reflects the interplay between Irish lake fishing and British club angling, an exchange that shaped the future of the sport.

The Letters & Their Legacy

This collection offers a rare, first hand account of fly-fishing during its golden age. The letters detail: catch reports, trout weights, locations, and successful fly patterns. Fly hatches, mayfly, olive, sedge, and other key species. Lake conditions, water levels, seasonal changes, and wind patterns. Trout behaviour, feeding habits, fly design experiments, and observations on perch fry. Personal anecdotes, wartime reflections, friendships, and humorous exchanges

Together, these writings form a vivid portrait of a place and a community devoted to the craft of fly fishing. Practical, poetic, and rich with insight, they capture not just what worked, but the experience of fishing Lough Arrow.

A Note to Readers

Painstakingly transcribed from exact copies of original manuscripts, these letters preserve a vital piece of angling heritage. Some words and names were lost to time, due to fading and handwriting style, but every effort has been made to retain their meaning and tone. This collection stands as a lasting tribute to the anglers, the lake, and the legacy that cemented Lough Arrow’s place as a proving ground for modern dry fly tactics on Stillwaters.

Extract from Henderson's Diary May/June 1907

Letter from Mosley to Henderson 23rd June 1914

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 20th June 1915

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 25th June 1915

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 13th August 1915

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 31st May 1916

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 17th September 1916

Letter from Brooks to Henderson 30th May 1918

Letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson 30th June 1918

Letter from Kingston to Henderson 22nd June 1922

Letter from Kingston to Henderson 15th June, year unknown

Portion of letter from Hinchcliff to Henderson, date unknown

Links to Letters

The Islands of Lough Arrow

Tommy Flynn, John Conlon and Mick Gildea swimming a cow to Gildea's Island

Lough Arrow is home to three large islands: Inishmore, Annaghgowla, and Inishbeg, known locally as Gildea's, Lyttle's, and Flynn's. These names reflect the families who once lived on them. Today, houses still stand on Inishmore and Annaghgowla, where the Gildea's and Lyttle's lived, but the Flynn home on Inishbeg is no longer there. For generations, these families lived on the islands—farming, fishing, and raising families in a unique and challenging environment. This is the story of those islanders: the Gildea's of Inishmore, the Lyttle's of Annaghgowla, and the Flynn's of Inishbeg.

Gildea’s Island – Inishmore

Inishmore, often called Gildea’s Island, is the largest of the three, with 46 acres of good farming land. James and Mary Jane Gildea moved to the island in the early 1900s. They raised four children—Jack, Mary-Jane, Annie, and Katie, on the island without electricity, phones, or engines. Everything had to be done by hand and boat.

The Gildeas were hardworking and self-sufficient. They rowed everywhere, farmed the land, raised animals, and fished. Jack, the eldest son, became a respected boatman and ghillie. He later bought the island himself, carrying on his father’s legacy. Life on the island was not easy. James was once mistaken for an IRA member, and soldiers fired shots at his boat. After his death in 1929, Mary suffered a breakdown and was hospitalised for many years. The children had to manage the island on their own and learned responsibility quickly.

Jack later married Mary Looby, and they raised four children on the island until moving ashore in 1960. Their move marked the end of a remarkable chapter in island life, but the Gildea name remains strongly connected with Lough Arrow. Each September, club anglers fish for the Jack Gildea Memorial Cup, which is presented by Jack’s daughter, Collette Noone.

Jack Gildea on his horse

Jack Gildea on Lough Arrow

Lyttle’s Island – Annaghgowla

Annaghgowla Island, also called Lyttle’s Island, was home to the Lyttle family. They lived there without electricity or engines, doing everything by hand and boat. They were self-reliant, farming, fishing, and cutting turf. They even built their own sawmill from an engine brought piece by piece from Carrick-on-Shannon by donkey and cart, then assembled it on the island.

The Lyttle's worked hard but were also known for their warm hospitality and kindness to neighbours and visitors. In winter, the lake sometimes froze, cutting them off from supplies. Once, a stranger was caught on the frozen lake and taken in by the Lyttle's until the thaw. The family remained on the island until 1973, when the last members, Tom and Gracie moved to the mainland.

Photo of Tom and Gracie Lyttle in 1972

Flynn’s Island – Inishbeg

Inishbeg, also called Flynn’s Island, was home to the Flynn family since the 1740s. James Flynn, his wife, and their seven children lived there until 1909, when they moved to Derrywanna. They had eleven fields and grew crops like potatoes and oats. Tommy Flynn, one of their sons, became a local legend. A skilled fisherman, storyteller, and boatman, Tommy was well known across Ireland. He hired boats and engines from his home at Arrow Cottage, across from what is now known as Flynn's pier. He proudly said he had “Ireland’s largest fleet.” and at one point, Tommy had 36 boats. He was often seen feeding swans at Flynn’s pier, and his pet swan “Johnny” would come when he whistled. Tommy’s father had a donkey who used to go fishing with him, it was common to see James Flynn and his donkey out fishing in their boat, the Green Drake.

Tommy also made fishing rods and even gave a gift of one to the Queen Mother after he was invited as a guest to the Fly Fishers Club in London. Visitors came from all over Europe to fish with him. He could predict the start of the mayfly hatch by watching a lilac bush bloom outside his cottage. Tommy died in 1997, but his stories, and deep knowledge of the lake are still fondly remembered.

James Flynn in the "Green Drake" with his donkey in 1906